[Video of this presentation is also forthcoming.]

[Transcription also available in PDF.]

[Please note, unless otherwise specified, poetry is presented with published line breaks:

for proper spacing and formatting, please consult printed source.]

Volume I

Edited by Emily DuBord Hill and Erin Lord Kunz

2014

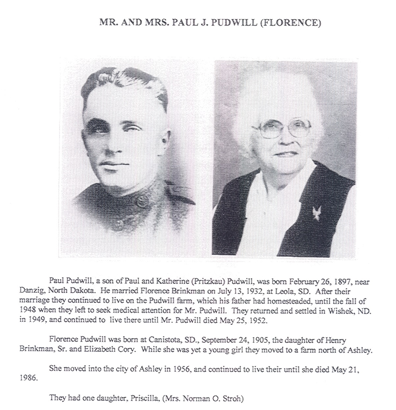

A special thanks to Art Grove, Monica Perkerwicz, Duane Kargel, Delpha Berg, Casey Whitman, Raymond Sevigny, Priscilla Stroh, Bill and Ruth Hill, Gene Lautenschlager, Paul Howard, Anna Marie, Clarence Olson, Ralph Waterman, Lavonne Brown, Valley Memorial Homes, The Community/Knight Foundation, and Crystal Alberts and the University of North Dakota Writers Conference. Thank you to all of our friends and family who have generously supported us and listened to us talk about this project for months.

Index

I. Shadows of a Small City, by Rachel Piwarski

II. Parachute Lessons in the Red River Valley, by Sam Rocha

III. The Hills, by Emily DuBord Hill

IV. Coming Home, by Alex Cavanaugh

V. Remnants of His Love, by Alek Haugen

VI.A Simple Story, by Anna Claire Tandberg

VII. Honeydew, by Erin Lord Kunz

VIII. Open Spaces are for Ghosts, by Laurel Perez

IX. The Best Part, by Sara Tezel

X. A Happy Man, by Dylan Schnabel

XI. Idled Memories, by Rhiannon Conley-Pierson

XII. For Eleanor, by Erika Gallaway

Introduction

This project began one morning with an idea and a question—how can we bridge the gap between the millennial generation and senior citizens in the Red River Valley region while creating a community art project? After several conversations between friends, a generous grant from the Community/Knight foundation, and the go ahead from the UND Writers Conference, the project came to fruition. We were going to create a collection of stories that delved into the lives of local senior citizens, written by local millenials. Every citizen has a wealth of knowledge and a story, and all stories can become works of art.

We cannot show enough gratitude to the writers of this project who were so intellectually generous, taking time out of their busy schedules to volunteer for a non-profit community project. Our writers showcase the ingenuity, dedication, and philanthropic spirit of the millennial generation. They all come from different backgrounds, spanning from university students to university faculty and everywhere in between. We believe that one strength of this project is the multiple perspectives and writing styles of all the participants, and we made the decision to not make the stories conform to one another in content, style, or aesthetics. We hope that you enjoy not only the stories themselves but how each writer crafted the story according to his or her artistic license.

Thank you to all of you who took the time to come to the Writers Conference Reading and to those of you who purchased a copy of the collection in your hands right now. All proceeds from this project go back to the UND Writers Conference, which we hope can continue as long as possible as another opportunity for community engagement. This project started with one idea and was made possible by the generosity and creativity of the Grand Forks community. We cannot express enough gratitude for your support.

Yours,

Emily and Erin

I. Shadows of a Small City

by Rachel Piwarski

The wind whipped across the plain and it brought the kind of chill that reaches into the human body and robs it of all its warmth. The snow reflected into the sky, making it a blue so pale that it was almost white. Larimore was a quiet town in eastern North Dakota, and it whispered with hopes of a pleasant spring to come, but the last warm day seemed too far away. As Hazel and I drove down West Main Street to see Anna Marie, I watched the few buildings fly by in a faded orange haze of brick and cement. We approached the stop sign and a window on the left laughingly displayed stacks of Pabst Blue Ribbon cans next to an American Flag. The occupants must have had a meticulous plan to craft their treasures so perfectly within the geometry of the frosted window.

In Larimore's Good Samaritan assisted living home, you wouldn't know such a bitter cold existed with its comfortably warm halls and smiling faces. The wind murmured occasionally against the building, but Anna Marie paid it no mind in her modest room. A shadowbox adorned the wall above her entertainment center and I stood staring at it, entranced like a magpie. Inside, a red velvet sheet of fabric bore fashion jewelry that made up a Christmas tree shape. In between the ornate earring pieces, tiny lights in the shape of flowers bloomed through the red in the spectral colors of the holiday season.

"Well, look at that," Hazel gasped.

"Yes, I made that, years ago," Anna Marie said, "I kept rearranging it over and over again to get it just right," she sighed in remembrance before she chided, "have a seat, have a seat."

"Where did you come up with an idea like that?" I asked as I moved a stuffed monkey with a medallion and realistic brown bear from her rocking chair to take my seat.

"I used to sing at weddings and funerals and things and the families would give me those clip-on earrings or other sorts of jewelry for me doing it, so I glued them into this shape on here and had Delmar drill the holes for the lights. Years ago."

So on a subzero January afternoon I came to visit Anna Marie in the middle of her Sunday devotional. I offered to sit with her until she finished, but she objected.

"No, that's okay. Let's go down to my room and visit," she smiled.

She revved up her Hoveround only to crash into the wheelchair next to her.

"Oh! Anna Marie, do you need some help?" the woman leading the devotional asked.

"I'm fine, dear," she huffed, "Just need to get turned around here...ahh, reverse."

She smashed into the table behind her. Forward. Crash. Backward. Crash.

"Uff da," Anna Marie mumbled.

Hazel and I stared with wide mouths and wide eyes. Hazel let out a throaty, nervous laugh. Here we were, the ultimate sinners on Sunday interrupting the devotional to talk to Anna Marie. The music stand wobbled as Anna Marie flew by it.

"Let us help you, Anna Marie." Hazel motioned for her to stop, but Anna Marie propelled forward.

"Here we go."

She shot through the doorway and into the hall, her blanket trailing in the wind of the Hoveround's momentum. The sleepy eyes of the residents stared at us, puzzled.

"Bye everyone, Enjoy." I waved before dashing off into the corridor after Hazel and Anna Marie.

When we arrived in her bedroom Anna Marie announced, "I don't know that I have much to tell, really."

From devotional to supper to bingo time, Anna Marie sat at a table surrounded by other women in cat and bird shirts in wheelchairs. This life signified a quiet simplicity the young yearn for when they leave the nest to the big, wide world. After birthing five girls, adopting one son, and tending to various farmsteads all throughout her life, Anna Marie finally had a place to rest.

"It's nice to finally talk to you. You're Adam's girlfriend?"

"Yes." Silence followed before I blurted, "Do you like it here?"

"Sure. I don't want to be all complaining."

"How's the food?"

"Oh no. Oh gosh. I can't complain. Well, the soup—no, I can't complain. I just wish I could be back in my kitchen sometimes. You know what I mean."

"In local cookbook publications you will find Anna Marie's recipes," Hazel chimed in.

"Oh yeah?"

"Yes, she can cook very well. "

Anna Marie turned a menacing eye Hazel's way. "I wish I could get back in my kitchen, but I don't know if I would remember what to do."

She rubbed her knees gently in circles as she talked; ornate rings caught the white light streaming in the window. A silver with turquoise ring sparkled like one of the pendants in the shadow box tree.

"What was your favorite thing to make?" Hazel's words cut the silence.

"Crackerjack."

"Like out of the box?

"Well no, because I made it. She then turns to me and said. "I'm sorry but after all this time I forget. Your name is—"

"Rachel."

"Rachel. Okay, good. I have seen you before, but it feels like I am finally meeting you."

"Yes, finally."

"And it's good to finally meet you."

"You too, Anna Marie."

After the quiet lingered again for a time, Hazel said, "Rachel wanted to ask you a question about how kids aren't what they used to be, and it's certainly right in a way. There are so many things that older generations don't approve of in terms of music and work ethic and things. What did your parents worry about with you and your generation when you were a kid?"

"Yep, I wanted to ask that question," I sighed to myself.

"What's that, Rachel?"

"Nothing. So what did they worry about, Anna Marie?"

I expected Anna Marie to tell me that her parents worried about the music she listened to or the dances she attended, but instead she answered:

"One thing that scared my parents was us kids riding our bicycles. I would come rolling down that hill and I would crash and scrape up my knees. One day in the summer they went to town and left all of us kids at home. We didn't have school, but we had chores and things to do. Myrtle was mopping and I sat at the top of the stairs singing "Myrtle and Johnny k-i-s-s-i-n-g because she started going with this boy. He must have been a junior. She hit me with that mop and chased me out of the house and I hopped onto my bike. She kept trying to get me with that mop, so I tried to get away. As I started to go, though, I crashed into the barbed wire fence. I bled all over as my parents pulled up."

"Oh my God! Did they take you to the doctor? Did you need stitches?"

"Oh no. We didn't have the money for that. If you got hurt, oh well. You broke an arm? It'll heal. But I did run into that fence, and of course I was bleeding, but I got fixed up well enough and here I am."

I pictured her crashing her bicycle with the same fervor as the way she crashed her Hoveround in the front room upon our arrival. I thought about her as she biked around a farm town with green grass glistening in the sun until it went down at ten or so, when the birds stopped chirping.

"That's impressive. So if that was your elementary school days, what were your high school days like?

"Well not too exciting, but one year we went up to the teen canteen to dance and whatnot. It must have been seventy degrees and I wore a dress and so did all the other girls."

The sun peaked out of the clouds and the grass emitted soft green hues as it pushed its way through the brown, spiky earth that the compacted snow pushed into submission all winter long. It was March and it was nice finally. The snow started to melt in the mucky, muddy way it generally did in the burgeoning spring. It was the time of year when twenty degrees seems like a gift, but on the day of Anna Marie's dance, it was much warmer than that. Suddenly the sky turned and it got real cold and the sun went away and the clouds came out and pelted the land with snow. The rough shift in weather only serves as one example of the rough winter that ravages the North Dakota prairie without remorse.

"Dad walked up to the school and brought my snow pants. My legs would have frozen off otherwise. He brought all of us kids back home with the twine in his pocket."

"Twine?"

"So they could all hold on. We had to do that when I was a kid when there were blizzards out at the farm in Minnesota" Hazel answered.

"Oh. The storm was that bad? None of you could see?"

"No. And we could get lost and that would be it, you know? I heard a lot of people got stranded out in their cars and died because they didn't know the storm was coming."

Hazel didn't like the silence, but I was content with letting it sit. With letting the wind scream against the cold windows.

"Chores were important, right?" Hazel asked as she finally caved to her need to make conversation happen.

I didn't come for a lesson on chores. Growing up in an all-male household where my dad barely knew how to do his laundry encouraged me to do plenty of chores. I sighed.

"We had too many chores to have fun all the time, but we did do fun things every once in a while like pretend our rocking chair was a car or something like that."

Anna Marie didn't seem too concerned with chores either, in spite of all the sorts of things she had to take on in her adolescence and adulthood.

"So what did you do after you graduate?" I said, wanting to change the subject.

"Well I attended Mayville State for one year, and then I got married."

Hazel turned to me, "The fact that she attended college for even that one year was kind of...well, unheard of. It allowed her to go into special education and things like that."

"I don't know that I have ever thought of it like that—special education. I just love the kids. I love seeing them. People call it special education, but all kids are special," she said as her eyes lit up.

The conversation died down to a silence where the ticking of the clock took over, and I could not help but feel that I didn't know her any better. Not in the way that I had hoped. We all stared out into the white abyss, three generations of women separated by unique challenges and stories. Anna Marie rubbed her knees one final time. Her eyes like dark pools told me she may have had more to say. But Hazel yawned and I yawned and we got up and hugged Anna Marie. I rubbed the afghan around her shoulders and thanked her, for her insight, for her hospitality, for a glimpse at a life that may be mine a lifetime from now.

Weeks later I walked down Towner Avenue, the main drag of businesses in the dying town of about 1,000 people. Dust caked the windows of past tool, television, and novelty stores. A sign that read "going out of business" in small black letters frayed in the windowsill of the tool store. An old gas station that was painted all white sat at the end of the businesses close to a senior center, library, and dive bar. It was a ghostly structure like so many houses and building in this old town. The wind rattled through the rickety buildings, and I knew it was time to go home. When Anna Marie was young, all of this was open land that people built up. And now here it is, crashing backward and disguising itself in the prairie's bleak, winter oblivion.

Rachel Piwarski is a graduate teaching assistant in the English Department at the University of North Dakota.

II. Parachute Lessons in the Red River Valley

by Sam Rocha

"We had food, happy – we had a childhood I wish every child could have."

*

In the spring of 1880, four years after the Battle of Little Bighorn, following a miserable harvest, her father began the 500-mile journey north from his birthplace in Spillville, Iowa, to the Territory of North Dakota, along with twelve families, in covered wagons.

He was a young boy, not more than eight years old. These were Czech immigrants, first and second generations. Roman Catholics. Farmers.

They arrived in Grand Forks, a town of around 600 people, on the twenty-first day of May. The townships were still in flux, and land was being claimed all around. Nothing near town was available, so they kept moving north, along the Red River, and then west, to find ground that was not as prone to flooding. Upon settlement, the men returned to town to file homesteading paperwork. Those with a little money left bought a few boards for their shanties.

Their hardships were not in vain. Despite the debilitating and torrential rains and the mosquitoes, a small planting of potatoes, brought from Iowa, yielded a crop previously unheard of. The fertile Red River Valley would be their home.

Whatever resolve they found in the growing season was tested right away: the winter of 1880-81 is on record as being one of the longest and hardest ever, with multiple blizzards hitting from October to February. This was before the rotary snowplow.

The first house built burnt down a few years later. All they managed to save was an upright piano. This sent the family to live in the granary until a new house could be erected. But these sorts of struggles were routine, easily fixed by hard work and the dogged spirit that brought their people from Eastern Europe to the Northern Midwest of the United States of America.

*

Her father played the coronet in a band, with relatives and locals. "I wish they had recordings of some of that music," she reminisced. The band would practice in a circle. The kids ran around and around, dancing.

"We only went to town if we needed shoes. I was the third one down, so I hardly got to go because I always had hand-me-downs." In the first grade she wore high-tops, but couldn't recall where she got them.

The long winters were spent playing cards and, on Saturdays, listening to the radio. The Grand Old Opry was her program, on short wave, with differences in broadcast quality, but she was always listening, faithfully.

All her brothers served in the US military. One of them died in the Korean War. It took two months for notice to arrive, in a taxi, leaving her father, downstairs, in tears. It would not be her last loss, but she wears the pain with grace.

*

Veseleyville was the Czech settlement, the area claimed in the 1880's, northwest of Grand Forks and southeast of Grafton, with a Catholic Church and a two-room school. The language of home, on the farm, was Czech, but school was taught in English, by a bilingual Czech-American couple. Daily mass was in Latin. The day-to-day routine began with a commute to Mass and was followed, after a short walk, with school. When her teachers moved away to Grafton, just a few miles northeast of them, they might as well had been going to San Francisco. She stayed in school until the sixth grade. High school was further away and costly. Houdek was her last name.

Monica Perkerwicz took a Polish last name, from a young man she met where all the young folks—Polish, Czech, and the rest—met at that time: the dance hall in Acton. The local church was struck by lightening, and burnt to the ground, moving the sacred Catholic Mass into the secular town hall. Monica and her now late husband, Rafeal, were married there. Her sister, Cyrilla, married her husband's brother, Chester, just before the church burnt down. Two Czech sisters married to two Polish brothers.

They both tried out living in California at different, but consecutive, times, and both returned north. From 1978 forward she raised her family alone.

*

The flood came in 1997, the same year she lost her daughter to cancer; she stayed in campers Crystal City Sugar set out for their employees, when they weren't back at work. Still in mourning, she set her things on top of tables that would eventually be completely submerged in water.

*

Her eyes lit up across the table, after the sad and hard times of '78 and '97. She said, "Mom and Dad got hold of a parachute."

"A parachute? Did you say a parachute?" I couldn't believe it. A shocked grin took hold of me at the totally unpredictable segue that arrived without warning. A parachute?

The parachute was bombastic.

"Lots of durable fabric," she explained. "Many slips made from that parachute material."

No skydiving involved, nothing too special or bizzare, but a parachute nonetheless.

*

Imagine a world where a single parachute is enough to interrupt the norm.

Imagine a time where things like textiles are luxuries, not vanities.

Imagine an age of hard living, no romance of good old days gone by. No. An era of work and work and more work and harder work over and over again. A period of limited resources, where temporal and material things are not eternal and shopping is not a religious devotion.

Imagine a place that is not imaginary, but seems to be far away because there is today a great distance, it seems, between my keyboard and the Facebook notifications that interrupt my headphones that are streaming YouTube music. Technology is not the difference here. If anything, this story is one where things were more technologically advanced because those first technical instruments, the hand and the back, were not as neglected.

This fantasy is easy to forget as part of the real, the real place and community and people and dirt and water that will soon thaw-out, swell, and flood, that boundary as arbitrary as it is indomitable: the Red River of the North.

This river knows more than we do. Its memory is long and deep, much longer than pioneer settlers and American Indians and deeper than a nation-state. The current runs along a different path than most, tilted upwards by foundations that are beneath, moving at a pace that chastens our quick and narrow life today.

*

The story sounds like any other story, really, and that's the point of the parachute. Ordinary stories don't get told unless we have something to gain from hearing them – or unless we are talking to ourselves. The river runs without melodrama, it is unconscious but alive, and teeming with life and catfish. But these lives that come and go hold something within them. Delight. It is not the plastic sort that scrubs everything clean and kills as much as it preserves. There is a simple, quiet, joy that can be found in the story of Monica Perkerwicz.

She loves to dance.

The whole point of the details – even the ones I left out – was that she wishes that kids today could have the happiness she knew as a girl. Notice, she does not long for it herself now; she is not suffering from naive nostalgia. Rather, she seems to see something missing in the lives we live today, something empty and absent that she never missed. She has known suffering and worked hard all her life, she knows loss and pain and heartbreak. And, still, it is she who has pity and empathy. There is no self-pity in this woman's heart. None.

And she's right: there is something she has that we've lost.

Where did the parachutes go?

*

"By today's standards," she recalled, "I guess we would be considered poor." She went on, with pride and resolve, "But we didn't know it."

"We had food, happy – we had a childhood I wish every child could have."

Sam is an assistant professor of educational foundations and research at the University of North Dakota.

III. The Hills

by Emily DuBord Hill

As I walked in, my grandparents are in the usual positions. My grandfather sat, hunched over in a wheelchair with a blanket draped over his back and shoulders. His rough hands together, smoothing out his purple veins with every half-asleep breath. He listened to the Grand Forks City Council meeting on TV. My grandmother sleeps solidly in her chair with the sunrays from the window warming her face.

They stir when they hear my dog's tags jingle as we walk in. Now, in their nineties and married 70 years this April, Bill is almost completely blind and Ruth has aches in her knees and hips. Together, they make a whole.

Sitting down with some cookies and coffee, we began talking about their history and the town they call home. The stories are the same from when I listened to them tell their lore while I sat on the carpet in front of them in their home on Almonte Avenue. However, when listening to these stories as an adult, suddenly their stories become relatable, haunting, romantic.

When asked about how they met, they both paused. Ruth smiled and said, "I think we've always known each other."

Bill was the only child of an independent widow named Helen. His father was a railroad man—never a conductor but he built the rail others traveled on. In 1921, when Bill was only two years old, his father came to his death at a young age. The cold days and nights working on the Northern railway a few miles outside of Grand Forks poisoned his father with consumption. In those days, when unexpected tragedies like this happened, extended families found it difficult to keep track of each other. Their ties to his father's side became blurred and broken. For most of his childhood, it was just Bill and Helen living in their house on Conklin.

Ruth was the daughter of Alexander McDonald and his wife Stella. Alexander owned McDonald's Fine Men's Clothing store, the only other men's clothing store besides Silverman's in Grand Forks County. Differing from Bill, Ruth grew up in a busy household with two sisters and two brothers and was raised in a now historic house on Reeves Drive.

In those days, neighborhoods blended with other neighborhoods giving children a large playground of friends to make. Bill and Ruth remember each other from these childhood outdoor games but it wasn't until they attend Grand Forks Central high School in 1935 that their friendship grew.

In those days, neighborhoods blended with other neighborhoods giving children a large playground of friends to make. Bill and Ruth remember each other from these childhood outdoor games but it wasn't until they attend Grand Forks Central high School in 1935 that their friendship grew.

Looking at pictures of my grandparents when they were young, the only way to describe them is Hollywood misplaced in Grand Forks. In almost every picture I've seen, Ruth's strawberry blond hair is swooped up on the side of her face with a nearly perfect smile. Bill's sparkling baby blues and thick waves of hair makes him her perfect counterpoint. When interviewing them about 80 years later, Bill still remembers the excitement that surrounded him when Ruth asked him to the sophomore dance. "After that, we've been best friends ever since," he said as he laughed.

They went steady all the way through high school and even went to the University (that's what they've always called UND as if it were the only one in the world) together. He was an ATO and she was a Delta Gamma. He was going to be an engineer because he was good with numbers and had hands like his father. He wanted to build bridges, tunnels, and railways. She was going for a teaching degree in hopes of teaching English and Home Economics.

"Oh we had so much fun at the University," expressed Ruth. They both remember going to Sioux Hockey games when they took place in an arena called the "The Barn." Community members would leave work at four in the afternoon in order to get a good seat. Everyone would pack thermoses and sandwiches to eat as they shivered at the game. And the fans were as enthusiastic and devoted as they are now. "It was absolutely wild," said Ruth. They remember watching Fido Purpur play and coach and how he was the one responsible for getting the "hockey craze" started in Grand Forks.

Along with enjoying many hockey games together as a young couple, Bill and Ruth loved to frequent the music halls in town. "We were pretty good at the jitterbug and the waltz," said Bill. "We loved it so much, that eventually when we were married, we built a tiled floor in our living room so we could invite the whole family over for a dance."

After a few years of college and with the war demanding more men to join the armed forces, Bill had no choice but to enlist in the army and leave Ruth in Grand Forks while she completed her studies at the University.

Bill fought in the Pacific and Guadalcanal for about four years. And it wasn't the battle stories that he chose to share with me during our interview. It was the story of how he kept courting Ruth even though thousands of miles away. "I always found time to write Ruth a letter. I would number all the letters so she would know how many were coming." Bill paused and an impish grin melted over his face. "That's how I kept the deal hot."

In March 1944, Ruth received a letter from Bill's station in the South Pacific. It expressed some romance and that he had been mildly injured in crossfire. He stayed in a hospital in Walla Walla, WA but would soon receive leave in April. But only for a week.

In March 1944, Ruth received a letter from Bill's station in the South Pacific. It expressed some romance and that he had been mildly injured in crossfire. He stayed in a hospital in Walla Walla, WA but would soon receive leave in April. But only for a week.

Ruth waited for Bill outside the train station in Grand Forks. When getting off the train, he embraced her immediately and proposed.

They were married on April 11th at St. Mary's Catholic Church, only a few blocks away from where each of them grew up. Because it was wartime, extravagance was considered unpatriotic. The church was not decorated; there wasn't mass, and only one attendant on each side of the couple. Bill wore his uniform and Ruth wore her new light gray suit. Her hair still remained swooped up on one side of her face, but all the other hair was gathered in the back, giving her a more conservative appearance. The wedding photo, even 70 years later, radiates happy, triumphant faces.

Since they were married and his station assignment was in San Francisco, the army said Ruth could come and live with Bill during his duty. The army set the couple up in a small house in Carmel. Ruth was fortunate to get a job as a secretary to the general while she was in California. She expressed her gratitude towards him because he let her continue working even after she became pregnant with their first child. "This was not always the practice in these days," she said.

Ruth also filled her time as being part of the Army Wives Club. Even sitting in her wheelchair many years later, you can tell this is a sore spot of her time out there. "When we would gather, we had to sit according to our husband's rank! Can you imagine?"

A few years later, Bill and Ruth watched their two-year-old son grow and play in sands of Carmel Beach. The both realized that the busy, noisy life of Carmel was not the place where they wanted their family to expand. "California was a good time. We met good people. But we knew we wanted to go back to Grand Forks. Grand Forks was our home" said Bill.

Bill decided to leave the army and move his small family back to the town of their roots. Being back in the Red River Valley, brought a new house, new careers and more children. The house on Almont Avenue was picturesque Americana: white, two stories, green shutters, and a balcony off the master bedroom. By the end of 1958, the family, which started off as two, grew into a family of ten. Bill's mother moved into their home after Bill's stepfather passed away to help out with all the children.

After arriving back to the town they loved, Ruth received a teaching job at Grand Forks Central teaching English and Home Economics. "I loved the young people and teachers at Central. In those days, you were not only the students' teacher but also their mother during the day" said Ruth.

But Ruth was not your typical high school teacher of the 50s and 60s. She was never one to sit on the sidelines and it would be fair to say she was a revolutionary educator. She noticed there was a hole when it came to teaching the art of cooking to college students. What was the point of practicing fine recipes without anyone to enjoy them? With the support from the administration at Central High School, Ruth implemented the first Home Economics Restaurant in North Dakota. At the time, the old YWCA was vacant and the city agreed for her to use the building's kitchen and cafeteria. Ruth still talks about this time with the excitement as if it were happening now. "There was an oven, fryer, even a dishwasher! The students and I invited every businessman in town. The most amazing part was that everyone paid!" This award winning program offered students the chance not only to cook delicious food for downtown employees on their lunch hour, but students also received the unique experience of practicing the art of etiquette and business before they graduated high school.

Bill beamed at his wife. "You can still go into Central and see her plaque. She was inducted into the Grand Forks Central Teacher Hall of Fame. Go through the door outside of the gymnasium. You'll see it yourself."

While Ruth made her career legacy at Central High School, Bill went to work with Ruth's father at McDonald's Fine Men's Clothing. He discovered he had a talent for sales. He also found an eye for quality-made clothing. During the 50s and 60s, it was high time for men's fashion. "I liked being part of it. There were so many customers and you got to know people from the community really well," said Bill. He worked for a grand store full of beautiful fabrics during a time when shopping was quite the event. Still to this day, even though he only has limited vision of the periphery, he can tell by touch if your clothing is finely made or not. Though he hasn't been downtown for some time now, he is proud of the fact that the McDonald's Fine Men's Clothing painted brick ad is still on the side of the building. Many engaged couples get their photos taken in front of it with very little knowledge of what is behind the ad—a family legacy.

No matter how busy they got with their careers, both agreed saying that they always thought of their children first. With seven sons and one daughter, there was never a dull moment in the Hill household. Some of their favorite family activities were to spend time out in their yard together. Bill built their children a large tree house in their back yard. The kids would spend hours up in the tree house, playing make believe, reading and writing plays. There was always something to do. In the winter, Bill would make an ice skating rink in their backyard. The kids and their friends never had to complain about a lack of excitement in the neighborhood.

In their retirement, Ruth and Bill focused on crafting and art. She sat outside in their screen house, painting watercolor scenes of what she saw in their garden and writing poetry. Bill spent many dark hours in the basement wood crafting anything from clocks, desks, frames for his wife's watercolors, various birds such as ducks and swans, two sleek California dolphins in polished walnut, and dollhouse furniture for his granddaughters.

His strong and craftsman-like hands became famous in the Grand Forks area, landing him a large picture and feature article in the Life section of The Herald in the 1990s. The reporter asked, "What was the first thing you remember making with wood?"

Bill folded his hands in his lap and thought as his new grandfather clock chimed. A smile ran across his mouth when he remembered. "The first thing I ever made was a sailing ship. The Santa Maria, all rigged out in linen thread. I got the plans from Popular Mechanics when I was about 12 years old."

"What other types of wood do you use?" the reporter asked as he sketched wildly in his notebook.

"Basswood is the best for my duck and swan carvings. It's soft wood and you can put in a lot of small detail," he crossed his legs in the chair he was sitting in. "However, I prefer hardwood, black walnut is my favorite. Oh, and cherry. It has to be hardwood if you want to appreciate the wood."

The reporter suggested he should sell his carved birds at art festivals because "They look as if they are ready to take flight." But Bill's artistry was never a business. It was for his family. It was his goal that every one of his children would receive a handmade clock or at least something crafted by his hands.

Now spending quiet days together in a nursing home, they tell me they are still "buddies." It is amazing to think about how much history a married couple can make in one North Dakota town. Even though both are overwhelmed about the amount of city expansion they've witnessed over the years, Bill says, "Grand Forks is still a wonderful place to live. It is as energetic and industrious of a city as when we were young." Although Bill and Ruth do not get out as they used to, it is still very important to them to be civically involved. They go listen to the newspaper being read every day. They are well aware of what is being discussed on the city council. They rarely miss a UND Hockey game on television. If there is one thing I've learned from listening to my grandparents' stories over the years it would be to love, cherish and know where you are from. During that afternoon interview, watching my grandparents sneak treats to my dog and boast with the nurse aids as they explained they were being interviewed for a big story by their granddaughter, I realized these near centenarians are unknowing pillars of the Grand Forks community.

Now spending quiet days together in a nursing home, they tell me they are still "buddies." It is amazing to think about how much history a married couple can make in one North Dakota town. Even though both are overwhelmed about the amount of city expansion they've witnessed over the years, Bill says, "Grand Forks is still a wonderful place to live. It is as energetic and industrious of a city as when we were young." Although Bill and Ruth do not get out as they used to, it is still very important to them to be civically involved. They go listen to the newspaper being read every day. They are well aware of what is being discussed on the city council. They rarely miss a UND Hockey game on television. If there is one thing I've learned from listening to my grandparents' stories over the years it would be to love, cherish and know where you are from. During that afternoon interview, watching my grandparents sneak treats to my dog and boast with the nurse aids as they explained they were being interviewed for a big story by their granddaughter, I realized these near centenarians are unknowing pillars of the Grand Forks community.

Emily DuBord Hill is the Co-Creator of the Voices of the Valley Writing Project. She currently works in the UND Honors Program as an Instructor and Student Life Coordinator and is the Executive Director of the Grand Forks Master Chorale. She is forever North Dakotan.

IV. Coming Home

by Alex Cavanaugh

It is a cool summer morning and the light is filtered through the trees and into the sunroom. The beds stir around the boy and he hears wet coughs and the nervous rustling of sheets. To his left another boy his age moans and turns over. To the right, the sheets are motionless. He presses the back of his head into the pillow and looks to the ceiling. The sun is warming his blanketed legs. The clock above the door shows 6:45—fifteen minutes until breakfast. He closes his eyes to sleep another five minutes.

He wakes, not knowing how much time has passed. The room has been cleared. He looks up at the nurse who gently shook his shoulder, and sees a doctor and another nurse standing over the bed next to his, the sheets and the body underneath still motionless. In another room a pan is dropped on the floor.

* * *

Art jerked awake, startled by a sound already far from his memory. It was dark outside and he sat up, allowing his eyes to adjust to the dim lights inside the tent. The stillness of the air around him was interrupted by heavy breathing and rolling in the beds around him. The room was filled with the sounds of men whimpering, snoring, moaning. He could smell the distinct odors of antiseptic and dirt. He laid his head back onto the pillow and closed his eyes, thinking of the warmth of the late summer sun in North Dakota.

In the morning Art was checked by an Army nurse, one of three making the morning bed checks. Some of the beds were now empty, but still positioned so close together that the nurses struggled to walk between them. This nurse, a woman near Art's age—25 at the time—checked his vitals and made notes on a chart. Her eyes had a distant look to them and it appeared her thoughts were elsewhere, escaping the repeated actions the work of the tent hospital demanded.

"Can you discharge me?" Art asked. Startled at this sudden interaction, the nurse looked at his face, which was young but did not betray the signs of experience. His skin was dry and tough from extended periods of time outdoors and long hours of work in the sun. His face, that of a young North Dakota farmer, had been further shaped by the work that surrounded war. Behind his eyes, though, she could see the return of confidence, of a will to move forward.

The nurse looked at the chart in her hand. "I wish I could." She looked at Art's face again. "You are looking better, though. Getting your color back. I'll talk to the doctor." Her eyes came into focus and she had returned to this room, to these beds with men missing limbs. Both she and art had witnessed enough of the men's agony to last both their lifetimes.

Art had spent those weeks in the tent hospital reading papers, sleeping on and off. He was drained, but steadily regained strength enough to move on his own. To pass the time, he kept up with the news of the war, of the Allies pushing the German forces back into Germany. He couldn't allow himself to become homesick—he knew that his survival depended on concentrating at the task at hand. Had he allowed his mind to wander, to dwell on the home he had left in North Dakota, he knew the war would catch up to him. Hospitalization was all the more difficult in light of this struggle. Art was stuck, incapacitated, left with no task to keep him busy other than that of his mind and memory.

Nevertheless, as Art became physically stronger he also gradually regained the ability to own up to his Army philosophy: he would have to be tougher than the men around him, especially those in his company. Art was the youngest man he knew in the regular Army, and the other men often referred to him as "the kid." This became so frequent that he formed a resolution that when the work became too tough for them, it would be just right for him. He would not let them break him. Art felt he had to grow up fast and grow up hard in order to prove himself to the other men. Now, though, he missed them, and saw them less as competition and more as peers, as brothers. After these three weeks away from his company, this group of wonderful men, he felt more alone than he had in some time.

That afternoon the doctor came to Art's bedside, checked the same vitals the nurse had checked this morning—Art hadn't seen her since—and authorized his discharge. He collected what few belongings he had with him: a shaving kit from the Red Cross, a toothbrush, and a set of dirty, worn fatigues.

He made his way from the series of tents that made up this Army hospital to the main road. Each tent was identical to the one where he had been the last three weeks, and Art realized there were hundreds, possibly thousands of young men brought from both sides of the France-Germany border that this part of the war had brought them to.

He regained his bearing and started walking to where he had last seen his company. When he had last seen the other men, he had been working on a crew tasked with repairing a Bailey bridge. Before this job, the company built a rest camp in Paris for recovering soldiers and those who had spent extended periods of time in combat.

At the bridge site, Art had been feeling weak, and his company commander, a man named York, placed him on sick call. He reported to the medic as per York's order. The medic, however, had a different assessment of Art's condition. "A big man like you," he said, "shouldn't be sick." Art returned to work and within the hour had passed out.

After Art had collapsed, York had instructed another soldier to drive him from the camp to the hospital in a weapons carrier. Art was unconscious during the trip and had only a vague idea of where his company was. He could only hope they were still there.

Soon after his arrival at the tent hospital, Art was diagnosed with Malaria. The nurses and doctors were quick to attend to him, assigning him to a bed in a large shared tent that was mostly full of injured soldiers. "What a mess I'm in now," he had thought to himself as he lay drifting in and out of consciousness, listening to the sounds of hurt and dying men for what would be several weeks.

Art walked about a mile and flagged down a jeep coming up the road. The jeep pulled up alongside him, the driver peering through the open passenger window. "Need a ride?" he asked. Tired from the lack of sleep and the lingering effects of his illness, Art didn't hesitate to get off his feet.

"Yes, please." He got into the jeep and the driver pulled ahead quickly, jerking the wheels back onto the road.

"I'm heading to the blockade. Is that where you need to go?" the driver asked.

"Yes, I think so. Do you know where the 370th Combat Engineers are?"

"I know where they are," the driver said, and the two men sat in silence a few minutes.

"Have you been in France long?" the driver asked.

"I've been all over." Art explained that he had come to the German border via Marseilles, and that he was in Corsica, Sardinia, and Algiers before that. In Algiers Art had been a part of the anti-aircraft crew that defended the naval base during its worst raid. That night, Bob Hope and Frances Langford were staying at the Aletti Hotel after visiting the soldiers at the base. When they had arrived they were assured by General Ike Eisenhower that Algiers was safe from German attack and that they would get a good night's sleep. A few hours after they addressed the men, the sky was ablaze as the anti-aircraft crews brought German planes out of the night sky one after another.

"I read about that raid," the driver said. "Where are you from?"

"North Dakota," Art said.

"How was the trip over?"

"It was all right." Crossing the Atlantic was the first time Art had been over a large body of water—he hadn't even swam in a river. As he was crossing the gangway onto the ship, a sailor had asked Art if he was scared. "You bet I am," he said. The sailor smiled and told him to follow the movement of the boat as he walked. "Walk with the waves," he said, "and you'll be okay."

During the voyage, there had been an attempted torpedo attack. Though the attack failed, several of the men lingered above deck, ready to jump overboard should the boat be hit. Meanwhile, Art heeded the sailor's advice and moved his body with the pitch and roll of the big ship, quickly adjusting to the lack of solid ground under his feet.

It had taken 13 days to reach the Mediterranean coast at Oran. There, the crew disembarked and travelled 20 miles overland by foot to Stony Point, where Art spent his first night on foreign soil. A young man from a farm in North Dakota, Art hadn't known blue as deep as the Mediterranean sea, or that palm trees could line highways.

The jeep was stopped by an MP at the blockade and the driver was informed that the vehicle was not authorized to pass. "I guess this is where we part," he said. The men shook hands and Art got out of the jeep. "What are you going to do?"

"I suppose I'll walk around the blockade and wait for my company," Art said. "Thanks for the ride."

"I'm just glad to help. Take care," and with a wave he drove off.

Alone now, Art knew he had to wait for a company truck to pass through the blockade. He thought of the driver, whose kindness saved him a fair amount of time and energy. Then he remembered the nurse, whose distant gaze struck him. Nurses, he thought, have the worst life in the war. He thought again of the men in the hospital that were brought in as he lay in his bed, unsure of how long they would be there, and of those that were there when he arrived and were still there when he left.

Art yawned, still tired from lack of sleep. His mind was still with the tent hospital, and invariably linked with another such period of uncertainty, years before, at the San Haven Sanatorium in Dunseith, North Dakota. When he was 15, Art contracted pleurisy and in July was taken to the hospital for treatment. Turning him over for long-term care was a difficult choice, but it was the only option available to his family. In the middle of summer, the farmers from Reynolds that bore and raised Art brought him North to the woods in the Turtle Mountains near the Canadian border and left him there. He spent six months at San Haven, and one morning awoke beside a tuberculosis patient who had died in his sleep. This was a constant reality at the hospital, where many of the patients died, their disease far beyond the scope of treatment at that time. Others spent years quarantined at the sanatorium in the woods, receiving treatment for the rampant disease. In Art's case, every day until December, when he was rid of the sickness and could finally return home, the doctors drew a pint of fluid from his lungs.

Art had a clear picture of that pint in his mind when a truck belonging to the 370th pulled up to the blockade. With the stillness of those woods around the sanatorium hovering around him, he approached the truck to rejoin his company.

Back at camp, Commander York called roll and seemed pleased to see Art returned and in good spirits. Taking Art aside, York told him it was good to have him back.

"It's good to be home," Art said.

"I'm sending some men to the camp we built in Paris and I want you to go with them."

"Sir," Art said, "I don't have a penny to my name, and all I have are these ragged clothes I'm wearing. I haven't been paid in three months. And there are men who need to go more than I do."

"Grove, this is an order," York replied. "I'll loan you some money and see that you get some clothes."

The next day Art was taken with the other men to the rest camp and over several days regained his strength. Though fall was approaching, the city was green and resonant with summer life. Art spent his time in Paris sleeping and walking in the sun, relaxing at the camp he helped build in the city that had not long ago been reclaimed.

After this period of recovery, Art rejoined his company and returned to duty. At this point the war was nearly over, and General George Patton's troops were in the final raids on the German opposition, which was at this point crippled and near defeat. Art was called into one of these raids for a dangerous mission—possibly the most dangerous of his entire tour of duty. Art was assigned to drive a truck loaded with fuel cans to tanks out in the field during combat. He later realized that had he, a clear target for any armed enemy, been hit, there would have been nothing left of him. Yet this task, which took place during Patton's final raid on Germany, was more dangerous than the various missions and challenges Art faced in the war. At present, though, it did not seem to him as ominous what he had seen in the hospitals, having recently witnessed the collective damages of war and having, as a young man, seen firsthand the scourge of tuberculosis. Each of these times he escaped death, and on the battlefield he managed to do so yet again.

Indeed, there were many points after Art first saw the Statue of Liberty as he left New York for the war that he doubted he would ever see it again. From the voyage overseas to the air raid in Algiers, the dangerous surroundings, the malaria, his final mission, and the return trip through violent weather that swept 22 men overboard, Art was astonished when at last he viewed the green figure rising tall out of the Atlantic.

In November, Art made his way from New York to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, where he was discharged, and travelled by bus to Minneapolis and then to Grand Forks. Grand Forks was in the snowless cold preceding winter as Art waited alone at a bus station for someone in his family to come for him. He called home and his uncle answered the phone, explaining that his parents had just gone to church and that when they returned they would come for him.

Art sat in the old bus station and waited, once again surrounded by the lingering quiet of certain North Dakota moments. These moments defined this place for Art, and they were what he knew he would always return to.

* * *

Art Grove was born in 1920 in a farmhouse in Reynolds, ND. He grew up on the farm and at age 15 was admitted to San Haven Sanatorium in Dunseith, ND with pleurisy. After six months of diligent care, he was released and he returned to the farm in Reynolds. In 1942 he was drafted into the Army and went to Europe in 1943. He served in Algiers, Sardinia, Corsica, France, and Germany. He returned to the United States after the war in November 1945. He married in 1947 and moved to a log house near Hillsboro, ND, where he farmed and raised livestock. Art's first wife passed away in 1950 and Art raised her son, whom he had adopted, until adulthood. Art married again in 1965. He and his wife retired from farming in 1987 and moved to Grand Forks, where he now lives.

Alex teaches composition at Lake Region State College. He lived in Grand Forks for seven years during his undergraduate and graduate study.

V. Remnants of His Love

by Alek Haugen

Words cannot do justice for the life of Raymond Sevigny. Though he can share from a seemingly endless wealth of beautiful stories, the words alone are lacking. They lack his infectious smile, his squinting, smiling eyes, and his spirit. At age 92, Raymond is far from the analogous mold of a fine, aged wine. Quite the contrary, in fact: He is a breath of fresh air. He is as spirited as he surely was as a young boy, riding his wagon through mud puddles on a farm east of Grafton, North Dakota.

Along with various chores caring for his family's cattle, chicken, ducks, turkey, and pigs, Raymond can share fun memories of his adolescence on the farm. Some of his favorite memories include working in the garden, playing "horse" with broomsticks, and playing hide-and-seek in the corn fields. On special occasions, such as when the family entertained company, Raymond's father would share with everyone from his storage of homemade beer in the basement. Everyone—no matter how small—got to have a glass of his father's beer. A parenting practice so contrary to the fears of society today, Raymond admires his father's trust and respect all the more.

Growing up in the 1920's and early 1930's, Raymond attended a Catholic School of the Nuns, the same school, in fact, as his father. Though Raymond loved school, he only received a seventh grade education. When discussing social, political, and theological ideas today, he is fair in raising the question: "Where do I get this information?" And his answer: "Well, I stopped to listen." Because of this history, Raymond holds a unique perspective on education. He is able to see that many people, though they go off to school, return unchanged. The problem, as he sees it, is that "they never get a sense of value." Only the briefest of conversations with Raymond is enough to prove that he values the heart much more than the head.

Raymond's story echoes of virtues and values waning in society today and tells of a way of life which is the unfortunate victim of progress here in the Red River Valley. He recalls days of freedom, days that were empty of worries, where three square meals were served (with real heavy cream, he adds), and no one—no one—worked on Sundays. According to Raymond, in making time for everything, our culture finds itself without time for anything. Raymond is one of the rare and wise who understands that stopping to visit with a neighbor is more important than finishing his work, an attitude which helps explain the depth and breadth of his relationships even to this day.

Raymond is the doting father of seven children—three daughters and four sons, of whom he has been blessed with 32 grandchildren. Raymond married his late wife, Sophie, in 1947, and she is still the keeper of the glimmer in his eye, his eternal dancing partner. The two used to love to get away, squander 25 cents for a dance ticket, and spend their night lost in Polka dancing. In fact, Raymond unknowingly first met his wife when they danced together:

"She claims we danced together, but I didn't know who she was," he recalls. "To me, it didn't make no difference who I was dancing with. When I came home [from the service], I went out onto the dance floor and I saw this pair of eyeballs. There she was. Of course, I always told the good Lord to give me a good woman. So, I got what I wanted."

It was a life of simple pleasures for Raymond and Sophie. Sophie's hobbies of fishing and boating were quickly adopted by Raymond. Their love for the outdoors often took the family on wagon rides to the country, where they would spend the day playing Frisbee and enjoying the fields. On the way home, they would stop at a country diner, and—when the children behaved—Dairy Queen, too. This was a favorite treat for the family, and one that Raymond often used as a threat...much to his amusement so many years later. Many of Sophie and Raymond's greatest adventures came during the twenty years they owned a motor home and used it to travel across the country. Among their destinations were Chicago, Milwaukee, South Dakota, and Montana. In one particularly humorous memory, Raymond recalls making an entire trip home from Chicago with a blown muffler. "Boy, was that a racket!" he laughs.

Raymond remembers these family outings with an obvious sense of pride and peace. Fondly, he remarks: "Oh, yeah. We had our days."

Raymond joined the United States Army in 1942 and returned home nearly four years later, in 1946. During his time in the service, he was stationed in Austria, Sydney, Brisbane, and, for two years, in the jungle of New Guinea. He still gets a genuine belly laugh when hearing the name of his company, abbreviated FARTC, which he and his comrades jokingly referred to as "Fart Company." Surprisingly, Raymond seems almost unaffected by his stint in the war. He is able to recognize that he "didn't go through Hell" unlike many of those around him, especially who suffered from malaria. One experience that did resonate with Raymond during his time overseas came in Manila when he met a young ten-year-old girl who sold the soldiers bananas. Her mother had been brutally attacked and killed by the Japanese and she was enthralled by Raymond and the U.S. soldiers. When he showed her a picture of his home back in America, she assumed he must be a millionaire and begged to go home with him. He still keeps the picture of that house in his desk.

Perhaps a more formative experience of Raymond's life came in the years 1951-1953. During that time, he and his family moved to Minnesota where he tried his hand at farming. Unfortunately—and quite simply—it was a bad year for crops. Raymond's crops were damaged by hail and, worse yet, he had no hail insurance. Then, the following year, Raymond's wife, Sophie, got sick. Struggling financially and emotionally, Raymond and his family were forced to lean on the assistance of others: "I had nothing left, but the thing is: I always had help when I needed it. No kidding. When I needed help, it was there. Mostly on my wife's side, but some were total strangers, too."

In remembering their kindness, these were Raymond's words: "If I was to pay those people for what it's worth to me, I couldn't earn it. No. I couldn't earn it." I would argue that that sentence alone is enough to summarize Raymond's ever-present humility and graciousness.

Raymond worked several jobs throughout his life. He worked for a time at PV elevator, for the railroad in Grafton, for Charles Adamson in construction, at a bank, and for thirty years at Vilandre Heating, Air Conditioning, and Plumbing. At his first job after returning from the service, Raymond was paid a mere $0.75 per hour. Before going overseas, he had spent the winters working for a farmer and earning $15 each month. Ultimately, he declined a $100 raise and the likely possibility of one day owning the farmland himself. His reason: "I figured the folks needed my help back home. It wasn't to be."

"A lot of people now-a-days are looking for the 'big money.' I never had big money. The good Lord always provided, so I give the good Lord room for that, because he always provided." Raymond draws inspiration for his simplicity from Saint Francis of Assisi and from the Pope, who bears the same name. He recognizes that most quests for success are based on competition, or as he explains it, "being able to buy everything the neighbors have."

"The 'big money' you make isn't always the best stuff," he concludes. "I'm not a rich man, but I'm happy."

Clearly, Raymond's faith is a most defining feature of his character. Motioning to his many prayer cards, he laughs: "But don't make me a saint, now." Though he fears that the world may be losing faith, Raymond remains devout. In all things—joy or suffering—Raymond gives thanks to God. Affectionately referring to Him as "the good Lord," the words are never far from his lips. He hardly acknowledges any so-called challenges in his life. "I just went along with it," he said. "I always depended on the Almighty." During the last years of his wife's life, for example, Raymond's patience and spirit were tested. Despite all the hardship, Raymond remembers it this way: "The good Lord gave me someone to take care of...and she was worth it."

If there's any warning Raymond would offer to the faithful today, it would be to ward off pride. He misses the traditional practices of the church, such as daily mass or blessing farmland and cars. He worries that people have grown too busy, or more aptly, that we've grown too busy with the wrong obligations. In fact, when he begins to explain why "It's too much pride," Raymond is brought to tears.

Raymond's love for his friends and neighbors at Valley Homes in Grand Forks, ND is also enough to bring him to tears. Though some at Valley Homes cleverly refer to Raymond as "Trouble," most of the many visitors who come through his door call him by name. "Now, that's not to brag about," he ensured me. "I appreciate it, though. People recognize me and I like that."

Raymond is able to acknowledge the good fortune in his life. Namely, he thanks God for his health. Despite his 92 years on Earth, he certainly does not feel old. This youthfulness is nothing new in Raymond; he claims that, at family gatherings, he was usually found playing outside with his grandchildren rather than mingling amongst the adults. Because he has been blessed with such persistently good health, Raymond takes every opportunity to care for those around him who have not been as lucky.

Raymond can easily recall several of the neighbors at Valley Homes who have impacted his life—all while he was surely impacting theirs. One in particular was a woman whose parents Raymond helped care for. She, herself, has suffered from Parkinson's disease for thirty years, and as Raymond remembers one of their most recent interactions, he cannot hold back tears. "She gave me a hug and kiss and, you know...It's working with these people. That lady appreciates it that I take care of her folks."

Another friend, a woman who lived down the hall from Raymond, left Valley Homes for another facility. Occasionally, he still sees her at church on Sundays, and—even after she has suffered a stroke—she remembers who he is and smiles when he playfully bumps her chair. As with all who know Raymond, she values his genuine friendship. "I was hoping you'd come," she told him at their last meeting. "They look up to me," he said of his neighbors at Valley Homes. Speaking of another friend of his, whose husband recently passed away and who was soon after diagnosed with cancer, Raymond remarks: "I get that lady smiling...and I like to see her smile. I feel good about it."

No, words do not do justice to the life of Raymond Sevigny. Words can only produce dates and places and timelines and list of accomplishments. But Raymond never needed any of those things... Instead, he lived a life of love. He never separated his heart from his beliefs, his family, or his work. Raymond's life is told by the remnants of his love, which surely live on in his happy and healthy family, his grateful neighbors and friends, a very humbled member of the millennial generation, and all those who have the pleasure of knowing his story.

Alek is a Bismarck, ND native who is currently studying psychology/honors at the University of North Dakota. She plans to attend graduate school for a PhD in clinical psychology.

VI. A Simple Story

by Anna Claire Tandberg

When I arrived at the Wheatland Terrace assisted living facility, I had no idea where I was supposed to go. Gene Lautenschlager had asked me to call when I got there, so I did. He didn't pick up right away, but once he did and we started trying to find each other, I walked around a corner and saw a man talking on his cell phone; I knew it must be him. I waved, he waved back. It was an interesting way to first meet someone. I smiled and introduced myself; he shook my hand. Gene had a nice firm handshake.

I asked where he wanted to do his interview and he led me to the activity center. We sat down at a table and started talking. There was a newspaper featuring a large picture of Julia Lipnitskaia, the 15 year old Russian figure skater, and an article about her. I asked Gene if he had been watching the Olympics; he had not. I told him what the article said about Julia, how she won the first gold medal for Russia and how everyone loved her. He told me he was proud because he has Russian heritage.

Then I asked him about his life. Gene was born in Berthold, North Dakota, which is a small town about 25 miles west of Minot. He was one of nine children. He went to school there in Berthold. Since it was a small town, his school went from 1st grade through 12th grade and not every class was offered every year. Gene told me he had wanted to take physics in high school, but it hadn't been offered at a time when he could take it.

Gene was never really interested in sports in high school—that was part of the reason he had not been watching the Olympics. When I asked him later if he ever did any dancing, even when he was younger, he told me he had been a "stick in the mud" and was far too bashful. Gene told me that he had been the smallest in his class so he had shied away from things that might have led to being teased. He reflected that his shyness became quite a handicap.

Gene told me he went skating once on a frozen little pond near the farm he grew up on. He related that he fell on his head, and that was enough skating for him!

After graduating high school Gene went to a teaching college in Minot. He quit after a year and a half, because, as he said jokingly, "they were trying to make a teacher out of me, and I didn't want to be a teacher!" I laughed along with him, and he revealed that he had only gone to that school because it was convenient. After that he worked in Minot doing office-type work. Then he was drafted into the Korean War.

I asked Gene what that was like and what he did. He told me he hadn't been in a combat unit; instead he was part of something called an observation unit. I had never heard of that before. He explained that his unit stayed close to the lines of battle. They watched the enemy and told the rest of the troops where they were. He was in the war for two years.

After the war Gene went back to college in Minot—to a business college this time. He graduated with a degree and worked for various businesses including an automotive dealer, a housing contractor, and a small electrical whole sale house. He stayed at the last one for nine or ten years. He told me he did a lot of bookkeeping for those companies. When I asked him if he liked what he did, he explained that bookkeeping came easily to him and he enjoyed it.

The last company Gene worked for moved to Williston and he moved with them. He was the manager there for four to five years when they started selling the company stock. Gene bought enough stock to own his section and became the owner of his own business. This is where he met his wife. In 1994 he sold the business and retired.

Sallyann was working for the company when Gene bought it. I laughed, and joked that that was a good way to get a wife! He told me he was about 40 years old when they got married so they never had kids together, however she was a widow and already had two children of her own: a boy and a girl. When Gene and Sallyann got married the children were already half grown. The boy was in junior high and the girl was a junior or a senior in high school.

Gene and Sallyann went on several business trips together, and before the kids went to college they came along on the trips too. They went to Washington State, Washington DC, Chicago, Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Saint Louis, and Hawaii, among others. He said Hawaii was his favorite because it was the most different. After the trip to Seattle the family took a car trip down the coast to Los Angeles. I asked him if he went swimming in the Pacific Ocean; he told me he had never learned how to swim but he did wade in. He confessed that he does not really like the water, and the he likes it much better when his feet can touch the bottom. I told him that my mom is the same way.

After Gene's father bought some land in Arizona the family went down to visit him. Gene and his wife also went to Florida at one point. I have always heard that Florida has alligators everywhere, so I asked if he had seen any. He had not. I asked him if he had ever been to Disney Land, he said he hadn't, but that while he had been in Florida with Sallyann they had gone to Disney World!

Gene said they went to Disney World in the second or third year that it had been open. I asked if he liked rollercoasters, and he told me that he and his wife did not go on any rollercoasters, and that there were not any rollercoasters there yet. He explained that Disney World has been developed a lot since it first opened. He told me he wasn't even sure if there were actors dressed up as the Disney characters at that point. Gene said they just went around sight-seeing and it was quite an experience. He stated that he and his wife had always planned to go back, but it had never happened.

I asked Gene if he had had any pets. He told me his family had had a dog when he was growing up on the farm and his wife had a dog when they were in Williston. They lost that dog, and got another. When they lost that dog they decided not to replace it because they wanted to travel, and if they went off traveling they would have to do something with the dog, and it would have made travel more complicated.

Then his wife got sick and they ended up not traveling like they had originally planned. In retrospect, Gene realized that they should have gotten another dog to help keep her company. He expressed regret that they had not. His wife was sick for 12 years before she died about two years ago. Gene became teary eyed as he told me this.

After his wife died Gene became sick. About six months ago he moved from Williston to Wheatland Terrace. His brother took care of selling a lot of property that had belonged to Gene, including his house, a cabin he owned on Lake Sakakawea, and some land. He still owns 80 acres of land that was given to him by his dad. I asked him how much that was and he explained to me that each farm section of land is one square mile. Each square mile is split into four sections of 160 acres. His father gave each of the nine children 120 acres of land. Since his father owned last in a variety of areas Gene's section of land is separate from the area of land where his grandfather homesteaded.

I asked Gene where his step children lived; he told me that the son lives in Grand Forks with a wife and three boys. He said they visit him often. The daughter lives in Williston with one girl and two boys.

Gene told me Wheatland Terrace is nice. They get three meals a day and he is getting healthier. When he first started staying at Wheatland Terrace he was renting a two room apartment. It was small, and he didn't like it very much, because it was so small. He admitted that if he would have had to stay in the smaller room he would not have stayed. He moved into a two bedroom apartment, and that was much nicer. He didn't know how some couples could stay in just the two room apartment; he thought it must be very cramped for them.

Every time some other resident would come into the room, or we passed them in the hall he knew who they were and he would talk with them. Gene explained to me how this assisted living place sort of worked. It is a pretty big complex that has both apartments to rent and a nursing home. An activities coordinator puts on a lot of activities for the residents. Gene likes to go to those. They play bingo, they have afternoon coffee, and they have sing-alongs. Gene told me he tries to sing along. Sometimes singers are brought in to perform for them. A woman also comes in and reads the news to them. They hold discussions about the news. She also helps them with different exercises that help with coordination and general fitness.

Gene reflected that even though there were maybe three hundred residents living in Wheatland Terrace, only about fifteen or so go to the activities. He told me that most of the residents stay in their rooms except for mealtimes. I thought this seemed sad. I was glad that Gene was not one of the people who just stayed in his room all the time; I was glad he got out and talked to people.

I asked Gene if there was anything he never did that he wanted to. He thought for a bit, then told me he had figured he would have traveled more. He had always wanted to go to Alaska, and he had wanted to see the east coast. He had been to Canada, and he had gone over the ocean to other countries when he was in the army. I told him that I am going to go to London over Spring Break, and that I would send him a postcard.

After we were done talking Gene asked if I wanted to see his apartment. I said sure, so he gave me a little tour. He showed me the dining hall where they all ate, since I had already seen the activity center he didn't need to show me that. His apartment was on the second floor and we took the elevator. The second floor has a big U-shaped hallway. Gene explained that since he liked to walk, and this hallway was very long, he would often walk from end to end. He informed me that he could walk around his hall three or four times and only see one of the women that help with the housekeeping.

Gene's apartment was very nice and clean. There was a walled off kitchen complete with all the kitchen utilities, such as a stove and fridge. He showed me his bathrooms, his office (which was one of the bedrooms, but he was using it as an office) and his walk in closet. He had lots of pictures on the walls of his living room and he had a television. I asked who the people in the photos were, and he pointed out his step children and his grand kids. There were a couple satin stitched pictures of a duck and a flower. I asked him who had made those and he told me his dad did.

After talking to Gene and seeing his home, we said our good-byes. I shook his hand again and thanked him for his time.

Anna is a sophomore at UND, currently studying Chemistry and Teaching.

VII. Honeydew

by Erin Lord Kunz

We'd been chatting for about twenty minutes when I relaxed into the sofa and took stock of my surroundings—paintings, pictures, the organized clutter of too many memories to properly contain. The house has an entryway leading into a receiving room with wood floors, a layout that treats company to their own space in the house during a time period when such care for guests was common practice. Casey Whitman had lived in the home for fifty years.

Throughout our conversation there was a massive brown dog sitting between us, and though lumbering and somewhat clumsy, it had not disturbed us since I arrived. She was sprawled out between my couch and Casey's, mediating the conversation and keeping an eye on us humans. I couldn't help but laugh when Casey told me that this wavy-haired giant's name was "Honeydew."

"Oh, she is HUGE," Casey said. "She has bumps and what have you all over because she is so old."

"Maybe like the dog form of wrinkles," I suggested, both of us laughing and admiring Honeydew.

As we sat talking in the receiving room, people came and went in a casual manner. A young man walked by in the background and Casey quietly said "hi dearie" in a relaxed inflection that suggested everyday interaction. I would learn later that her daughter Jean's family also lived in the house, which explained the warm and comfortable relationships in the home that are completely alien to my own familial encounters.

The family's ease seemed derivative of Casey's ease, who is the definition of pleasant--and not the unpleasant pleasantness, either, like the sort of Dolores Umbridge sugariness that makes your stomach twist. There was no training on how to treat guests kindly, just a genuine calm and absence of suspicion, another quality that was alien to my familial encounters.

I was certain I would have recognized Casey had I been at the grocery store, the gas station, or the park. She is the image of my friend plus 65 years, with the same bone structure, petite frame, and air of agreeable curiosity and welcome. It seemed comical—planned almost—that she was also wearing a blue flannel shirt, grey cardigan, jeans and blue sneakers, as if my friend's wardrobe had traveled along for 65 years as well. Casey is, in fact, my friend's paternal grandmother.

The elderly can be terrifying in the way children can be terrifying; blunt honesty has no time for feelings or political correctness. This was not my experience with Casey. She did not comment on my hair, the uncomfortable way my five-year old niece and 70-year old grandmother do; she simply said that she liked my hat. I was becoming suspicious about the lack of passive aggressiveness in this individual.

Because Honeydew's presence had declared it must be, our conversation was casual. Casey told me about her favorite food—chicken, corn, and mashed potatoes—as well as her least favorite food—tuna fish on Fridays, every Friday.

"I hate tuna. I hate it," said Casey.

"She really hates tuna," said Jean.

Apparently it will take a few more generations for us Catholics to realize the non-tuna options for no-meat Fridays. Casey doesn't particularly like cooking, and she said she got lucky because as she explained, "my mother was such a good cook so I didn't have to be." Casey's mother lived with her and her growing family, and now Casey's daughter Jean's family lives with her, in the same house on Reeves. Lots of familial history where I was sitting. Because of this arrangement, Casey never had to bother much with her meals, which to me sounded like an ingenious and life-sustaining plan.